The landscape surrounding the three-storey house in Primrose hill lies dead, silent save for the occasional sound of a motor’s hum. To the side of the house, the dark yard gives way to a small, uniform garden devoid of all life bar the hardy weeds struggling through the stubborn soil. Beyond this, and darker still, silhouettes of buildings rise up to break the sky’s fragile horizon. The sole source of illumination, except for a scattering of stars, is a low dull moon fuzzy with cloud. The nights silence fills the house, ruptured now and then by the sound of feet tapping deep in thought on wooden floorboards.

In the third floor bedroom two children, a girl not yet four and her baby brother sleep carelessly in their beds. Down the hall, in a second bedroom, a young woman sits hunched over her desk, a gift from her husband’s mistress, pouring her mind’s scrambled thoughts onto the page in front of her. Absorbed in her task, she is perched on the edge of her chair. Lines score the creases in her chalky face, testament to her troubled mind. Her frame is thin, too thin – she has been losing weight steadily now for a couple of months. A wisp of long brown hair falls into her face, tangled and unkept. She finishes her sentence, signs her name in small scratchy letters, and brushes the strand behind her ear with trembling fingers.

Her eyes, muddy with drugs, rise to the window beside her desk, looking past the skeletal shapes of trees to the tube station her husband would come from in the morning; to see the children and to ignore her. Sometimes she would stand there for hours hoping to catch a glimpse of him as he arrived. Her heart would flutter as she saw his strong jaw jutting out beyond his face, his dishevelled hair rising and falling in the breeze. ‘He is no longer mine’ she thinks, ‘I will fool myself no more’. As she recalls her last meeting with him a tear creeps out of the corner of her eye, rolls down her cheek and onto the paper.

‘Assia is pregnant’ he had said. ‘We’re going to have a baby’.

Her chest aches with the memory. Distracting herself she brushes away the spreading circle of wet on the page, smudging the pen, and folds each sheet of paper neatly into three. From the desk she withdraws a stack of crisp white envelopes and sets to work addressing them. As she writes, obsidian clouds gather in her mind. Hardly looking up, her fingers clasp around a small brown bottle. She fumbles with the lid, the contents rattling like an angry mob, before she pops it open and peers inside. It is nearly empty, but she knows she won’t need to get another prescription. Up-ending the bottle three pills fall into the upturned palm of her hand. ‘Two blue and one white’ she thinks, ‘not that it matters’. She swallows them – more out of habit than need, her depression lifted at the thought of what awaits her. She grimaces at the sour taste of bile rising in her throat.

Beside her lays a stack of poems, meticulously arranged by theme, the title page bare but for one word ‘Ariel’. Straightening them she places them in the centre of her desk. ‘My finest work’ she thinks, ‘what I shall be remembered for’. Opening the draw she searches, rummaging and mumbling to herself. Now angry she thumps her hand on the desktop. ‘Stamps!’ she exclaims fractiously. She was supposed to get them today but the combination of anti-depressants and barbiturates has made her memory fickle. She looks to the old clock in the corner of her room. 11.45. ‘Mr. Thomas will be awake’ she thinks ‘but not happy to see me’.

As she enters the hallway her pupils dilate, adjusting to the lack of light. Here, shrouded in darkness and hearing the soft breathing of her children from the adjoining room, she is calm. Gradually shapes begin to appear to her and her delicate fingers grope for the banister. She floats down the spiralling staircases; her pale hand tracing the wall till it finds the switch. Pushing it she brings to life the solitary flickering light bulb that illuminates the atrium.

Her hesitant knocking echoes in the large tiled room and she waits impatiently, shifting her weight from one foot to the other. Embarrassed, she remembers the last time she was here, banging frantically on his door, howling hysterically, with mascara streaming down her face in fat black rivulets. She had begged him to let her come in, having nowhere else to turn. He had sat with her patiently, offered her a glass of sherry even, as she related her husband’s infidelities, talked about his new woman with a womb of marble. She had shown him a review of her novel in the paper. He had been impressed, but not enough to shepherd her out of his flat as soon as she had stopped crying.

Eventually the door creaks open to reveal a man in his mid-thirties. His wiry frame is draped in a dressing gown and she can tell from the crimson of his cheeks that he has been sitting in front of the fire. His bony hands clutch an open book that he holds to his side. Through gold-rimmed spectacles his beady eyes search hers for the reason for this late night disturbance. He suspects she would once again like to unburden herself on him. As if he hasn’t enough problems of his own. He sighs.

‘What can I do for you Mrs. Hughes?’

‘Sorry to call so late, I was wondering if I could trouble you for some stamps. I have some letters that require immediate postage and…’ she breaks off, feeling the effects of the sleeping pills she took earlier.

There is something unusual in her eyes and in her voice that troubles him. With worry shadowing his face he retreats into his flat leaving her standing in the hall. As she peers through at his finely furnished front room, the warm glow of the fireplace calls to her. She longs to sit in the deep floral armchair, close her eyes and forget everything. To drown in warmth. To forget she exists. He reappears bearing a book of stamps.

‘Are you… Is everything alright?’ he asks.

She lowers her gaze, hiding her expression. He shuffles uneasily, not wanting to pry.

‘Should I call Dr. Horder?’

‘That won’t be necessary, I saw him earlier. How much do I owe you?’

‘Don’t be silly, it’s just a couple of stamps’. His face crinkles and he waves his hand as if brushing off a fly.

‘Oh but I must pay you, or I won’t be right with my conscience before God will I?’

She fumbles in her pocket and draws out a couple of coins. Placing them in his palm she half turns away then faces him again as if she has forgotten something. He eyes her worriedly; he doesn’t understand her last statement.

‘What time do you go to work in the morning?’ she asks.

‘Eight thirty’ he replies ‘Why do you ask?’

‘I was merely wondering. Goodnight Mr. Thomas’ she pauses. ‘And goodbye’.

Puzzled, he closes the door and continues with his book.

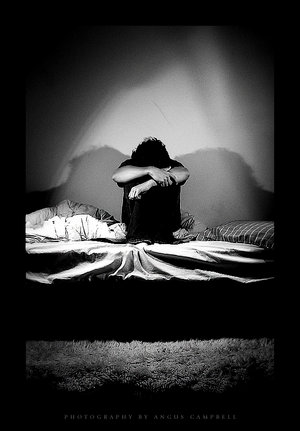

Alone in the atrium, the clouds return. One by one they are manageable, but now, together! Her mind is full of black thoughts buzzing, bumping, bouncing of the inside of her skull. She cannot control them, though she is their creator. Her brain a box of maniacs with no window, no exit. The bell’s incessant ringing, the pecking and the gnawing. Wave after wave crashes over her sucking her down to the depths of her depression, she struggles to reach the surface, drowning in despair and panic.

Now, a port-hole, a bubble, the Light. She thinks of the nothingness that awaits her, its sweet relief, emancipation! The clouds dissipate in the Light and she feels its brightness wash away all she knows. She aches for it, the tranquillity of oblivion.

‘She’s left the damned thing on’ he thinks, spotting the slit of light coming from under his door. Rising, he shuffles across the rich rug coating his floor and pulls it open. She is still there, the same blank look on her face she had twenty minutes before. Her eyes unfocussed she stares expressionless at him.

‘Are you sure you won’t have me call the doctor Mrs. Hughes?’

She blinks, takes a step back startled and her mouth drops open.

‘Mrs. Hughes?’ he asks raising a single eyebrow.

‘I was having a marvellous dream, a most wonderful vision’ she murmurs, half to herself. He nods, unsure whether to leave her or not. Her gaze returns to its vacancy. ‘I wonder what she’s taking’ he thinks, closing the door.

Now, decisive, she strides to the coat stand and puts on her long pastel coat. She wraps a scarf around her neck and braces herself against the cold. Clutching her letters to herself she opens the front door and steps out onto the shining pavement, dusted with the glimmering carpet of February frost. The night is dark and the cold air stings her skin under her clothes. She welcomes it, a pain that doesn’t come from inside her. It wakes her, combating the pharmaceutical drowsiness. With a keenly focussed tunnel vision she marches to the post box at the end of the road.

Back inside, she removes her scarf and brushes the glittering ice off her coat. As if in a dream she glides up the stairs to the unlit kitchen. Avoiding even looking at the appliance in the corner, she opens the fridge and the widening arc of light seeps out. Hands shaking, she pours two glasses of milk and prepares a plate of bread and butter. ‘What will Frieda and Nicholas think of me?’ she wonders. ‘They are too young to understand. Ted will think me selfish. Perhaps he will be a little sad, though I doubt he cares anymore. Did he ever?’ Shaking her head, she forces the thoughts out. The first time she was in a psychiatric ward they said she had trouble coping with abandonment. Her father first, now her husband. ‘What is wrong with me? Am I unlovable?’ Once again she shakes her head. She is in control now. She is the owner.

Gently she pushes open the door. The children lay still, their breathing mellifluous. A pang of jealousy rises in her; she longs for their ignorance, their irresponsibility. Their innocence and their serenity. Soon. She places the glasses and the plate on the floor beside their beds and pushes open the window, wedging a book in the gap to make sure it doesn’t close. Frieda has kicked her duvet onto the floor; she replaces it, bending over her daughter to place a single soft kiss on her forehead. Stifling a sob, she repeats the action with her infant boy. Her certainty is fading, she must act quickly.

Steeling herself against the doubt she knows will enter soon, she paces across the hall into the bathroom. In front of the mirror she stares at the shrunken reflection looking back at her. It challenges her, and she feels the uncertainty creep in. Reminding herself that she is strong, she buries the vacillation in her eyes. After washing her face and tidying her hair she opens the bathroom cabinet and removes the tape she bought earlier. Picking up the towels, she returns to the hallway, resolute. Pushing the towel meticulously under the door frame, she makes sure she has left no gap. Sealing the sides and top of the door with the tape, she runs her fingers over its smooth silver surface, pushing out bubbles. She takes the key from her pocket and locks the door, steadying her quivering hands. She leaves the key in the keyhole for whoever should come in the morning. She does not want them finding her.

The old clock in the hall registers 4.15am. The blue hour. The hour where she has written her best work; the hour when she feels least in control of the clouds. She glides down the stairs and into the kitchen, tape and towels in hand. She slowly repeats the process of sealing the door, equally thorough only this time from the inside. As she finishes an overwhelming wave of calm sweeps over her, her face, previously taut, relaxes and she almost smiles. Oblivion awaits.

Closing the window, for the first time she faces the oven. The dark clouds, the bees, are all appeased. They know their release is imminent. Dreamily she approaches it. Laying her hands on the cold steel, her fingers trace the contours of the handle, tightening. She twists and pulls, and it falls open. The gentle, sweet hiss of gas floods her senses. Folding the final towel into four she places it on the oven door. Sedately she kneels and rests her cheek on the cotton. The noise is silenced and all is tranquil.

On her death certificate, which was registered on the 16th, Sylvia Plath was described as being dead on arrival to the hospital. Her occupation was listed as ‘an authoress… wife of Edward James Hughes an author’. The cause of death was documented as ‘Carbon monoxide poisoning (domestic gas) while suffering from depression. Did kill herself.’ On a desk in a room at 23 Fitzroy Road lay a finished manuscript, Ariel and Other Poems.